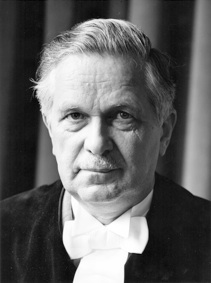

Erwin Stein

Prof. Dr. jur. Erwin Stein established the foundation in 1991.

The most important dates in his life are mentioned in brief: Born in 1903 in Grünberg (Upper Hesse) as the son of a railroad engineer; humanistic grammar school in Frankfurt am Main; studied law at the universities of Heidelberg, Frankfurt am Main and Gießen; completed his legal training with both state examinations and with a doctorate; until 1933 public prosecutor and judge at various Hessian courts; dismissed from public service at his own request in July 1933; Lawyer in Offenbach; from 1943 until the end of the war, he was a simple soldier; after the war, he initially worked as a lawyer and notary public in Offenbach, politically active in the CDU; member of the State Assembly for Greater Hesse, which advised on the constitution; from 1946 to 1951, member of the Hessian State Parliament, from 1947 to 1951, Hessian Minister of Culture and, from 1949, also Minister of Justice.

From 1951 to 1971, Erwin Stein was a judge at the Federal Constitutional Court, of which he was a member of the First Senate. He thus belongs to the founding generation of the Federal Constitutional Court. Among other decisions, he prepared three important rulings as rapporteur of his Senate: the one on the ban of the KPD, the one on Klaus Mann's "Mephisto" novel, and the "Rumpelkammer decision", which was groundbreaking for the development of the state-church law of the Federal Republic.

Together with the former Prime Minister of Hesse, Georg August Zinn, Erwin Stein wrote the important and so far only commentary on the Hessian Constitution, one of the first ever on a state constitution, and continued to edit it. He has written groundbreaking legal treatises, especially on school law and state-church law, has dealt intensively with questions of philosophy and art, was chairman of the Leopold Ziegler Foundation and president of the Humboldt Society for many years. From 1947 to 1953 he was a member of the synod of the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau, and later, when he lived in Baden-Baden, he was a member of the synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Baden.

His achievements in science policy are also worthy of mention, including the reestablishment of the Justus Liebig University in Giessen, with which he remained closely associated as Honorary Senator and Honorary Professor of its Law Faculty, and the founding of the German Institute for International Educational Research in Frankfurt am Main, where he served for four decades as Chairman of the Board of Directors and President of the Foundation Board. Moreover, Stein played an important role in Hesse as an elder statesman. It was he who in 1978 put an end to the fierce conflict over the Hessian Framework Guidelines by writing the "General Foundation of the Hessian Framework Guidelines". The then Hessian Minister President Holger Börner and the then Hessian Minister of Education and Cultural Affairs Hans Krollmann had chosen him as mediator - in the wise foresight that Stein was in a position to objectify the discussion because of his professional competence and because of the high reputation he enjoyed across party and group boundaries.

In this way, Erwin Stein has left lasting traces in the public life of Hesse and Germany. He died on August 15, 1992 at the age of 89.

This vita would be incomplete without highlighting one of Erwin Stein's traits: he possessed an unusual amount of moral courage. He exemplified the virtue of being an upright citizen, a citoyen: in the Weimar Republic, when courage was required to say "yes"; in the "Third Reich", when it took great courage to say "no"; and in the Bonn Republic, when it was necessary to distinguish between the right "yes" and the right "no".

He showed civil courage above all during the Nazi era. He did not allow himself to be seduced by the Nazi regime, not to be bent, not to be appropriated. However, he did not like to talk about these years later. But the experiences he made and suffered through then have become formative for everything he later thought and did. What were these experiences?

Erwin Stein was married to a Jewish woman, Hedwig Stein née Herz. He was not prepared to accept the imposition of the Nazis to divorce her. That was one of the reasons why he asked to be dismissed from the civil service, where he would have had no future anyway. For § 1a.3 of the Reich Civil Servants Law in force at the time, the notorious Aryan Paragraph, stipulated: "Anyone who is not of Aryan descent or is married to a person of non-Aryan descent may not be appointed as a Reich civil servant. Imperial officials of Aryan descent who marry a person of non-Aryan descent are to be dismissed." Thus Stein had to assume that sooner or later he would be removed from the civil service anyway. So it seemed only logical that under the given circumstances he decided to become a lawyer. It was not easy for him, since he was shunned because of his Jewish wife, whom he stood by and did not sacrifice for the sake of his career. After all, colleagues helped him by secretly having him write writs or expert opinions.

In March 1943, Mrs. Stein received a postcard from the Gestapo in Offenbach, asking her to report to the local Gestapo office. She did not follow this request because she knew what fate was destined for her. On March 23, 1943, she took her own life.

Against the background of this fate, it is easier to understand why Erwin Stein was so resolutely committed to building a free state after 1945, after the end of the Nazi era, which he truly experienced as liberation. He was a passionate democrat, open to the challenges of the time and at the same time firmly rooted in the Western tradition of Christianity and the Enlightenment. Tolerance and humanity were his guiding principles. In politically intolerant times he was a brave citizen with moral courage.